November 14, 2012

Slumdogs vs Millionaires:

India in the Age of Inequality

P. Sainath

Rural Affairs Editor, The Hindu

Visiting Professor of Journalism, Princeton University

Slumdogs vs Millionaires:

India in the Age of Inequality

P. Sainath

Rural Affairs Editor, The Hindu

Visiting Professor of Journalism, Princeton University

Minutes of the Eighth Meeting of the 71st Year

President Ruth Miller presided at the 8th meeting in the 71st year of the Old Guard, held on November 14, 2012.

Julia Coale led the invocation.

George Hansen read minutes of the previous week, when Ward Wilson spoke on the subject of rethinking nuclear deterrence.

The following guests were introduced:

Russ White, by David Egger; Ellen Kaplan by Michael Kaplan; Karl Zaininger by Glenn Cullen; Somnath Mukherji and Walter Lippincott by Lanny Jones; Alison Stevenson by Elliot Daley.

Attendance: 121

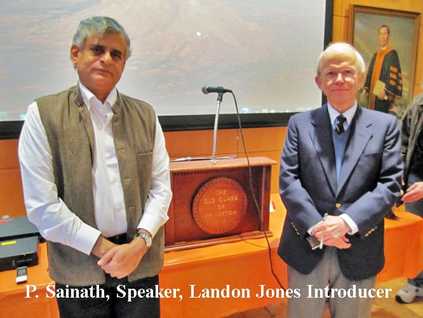

Our speaker, P. Sainath, Rural Affairs Editor of The Hindu and currently Visiting Professor of Journalism at Princeton University, addressed us on the topic of:

Slumdogs versus Millionaires: India in an Age of Inequality

In 1993, and already an established and successful journalist, P. Sainath came to the uncomfortable realization that conventional journalism always functions in the service of power, and he wanted no further part in it. To the incredulity of his colleagues, he applied for a Times of India fellowship in order to study poverty in India, what Sainath bluntly calls “the elephant in the room” of public discussion of India. His findings were published in a series of articles, the basis of his acclaimed book, Everybody Loves a Good Drought. His study tour of the ten poorest areas of the country covered 100,000 kms, using 16 different forms of transport, including 5,000 kms on foot. The book is still in print.

Sainath ironically juxtaposed statistics and tragic evidence of the cavernous—and growing--gap between the two worlds inhabited by India’s many millionaires and India’s poverty-stricken millions. He pointed to the same gap as increasingly characteristic across the globe, notably in the United States, where, as in India, enormous wealth now belongs to only a tiny sliver of the population as a whole. India ranks 5th for its number of billionaires (55 currently) while 860 million people barely survive on 50 cents a day. In one ironic aside, Sainath observed that while India sends its billionaires to Parliament, Russia sends hers to prison.

Yet a virtually criminal manipulation of facts and data consistently glosses over the reality of extreme poverty. Not only is there a major disconnect between what is deemed newsworthy and the plight of the vast majority of Indians, but even words and their re- definition have become tools of official policy.

Illustrating his contention that the “large canvas” global issue of our time is inequality, Sainath pointed to published annual statistics by the United Nations on how much could be done to address the issues of world hunger and sanitation with additional expenditure of only some $60 to $80 billion, yet lack of awareness and the absence of political will, allied with fierce dedication to stock market profitability, keep such investment permanently off the global agenda. Yet, in 2008, $32 billion was “grown overnight” by the US government to address the subprime mortgage crisis. This is a snapshot of what kind of a world we live in.

Eleven countries suffered especially calamitous devastation from the tsunami of 2004: yet of these, the five countries that had stock markets all hit historic highs within days after the tsunami struck. In the same week as 30,000 homes in Tamil Nadu were demolished by natural disaster, 48,000 homes in the slums of Mumbai were demolished by order of the government, a move met with widespread popular approval and encouraged by the mainstream media which praised “the destruction of this eyesore.”

Good journalism is to be judged by whether and how it addresses the major issues of the day. Sainath devotes his journalistic efforts to exposing the gross inequities that disfigure the “official” face of India; the ravages of agrarian policy for example are both the direct consequence of human intentionality and a damning indictment of India’s extreme inequality. Crime Records data, published annually and open for all to read, reveal the misery of the rural poor. 271, 000 Indian farmers have committed suicide (suicide is officially designated a crime) over the last 16 years, while the rate has so accelerated in the last 8 that there is now a suicide every 30 minutes. Pathetically, the suicide notes left by these “criminals” are addressed, not to their loved ones, but to finance ministers and banks, begging them to stop harassing farmers to pay up on their “debts,” debts driven brutally high by the application of exorbitant interest rates on loans. While a millionaire can obtain a 7% rate of interest for purchase of a Mercedes Benz, a rural farmer may be charged 14% on a loan to buy a tractor.

A lively question and answer session followed P. Sainath’s riveting account.

Respectfully submitted,

Joan E. Fleming

Julia Coale led the invocation.

George Hansen read minutes of the previous week, when Ward Wilson spoke on the subject of rethinking nuclear deterrence.

The following guests were introduced:

Russ White, by David Egger; Ellen Kaplan by Michael Kaplan; Karl Zaininger by Glenn Cullen; Somnath Mukherji and Walter Lippincott by Lanny Jones; Alison Stevenson by Elliot Daley.

Attendance: 121

Our speaker, P. Sainath, Rural Affairs Editor of The Hindu and currently Visiting Professor of Journalism at Princeton University, addressed us on the topic of:

Slumdogs versus Millionaires: India in an Age of Inequality

In 1993, and already an established and successful journalist, P. Sainath came to the uncomfortable realization that conventional journalism always functions in the service of power, and he wanted no further part in it. To the incredulity of his colleagues, he applied for a Times of India fellowship in order to study poverty in India, what Sainath bluntly calls “the elephant in the room” of public discussion of India. His findings were published in a series of articles, the basis of his acclaimed book, Everybody Loves a Good Drought. His study tour of the ten poorest areas of the country covered 100,000 kms, using 16 different forms of transport, including 5,000 kms on foot. The book is still in print.

Sainath ironically juxtaposed statistics and tragic evidence of the cavernous—and growing--gap between the two worlds inhabited by India’s many millionaires and India’s poverty-stricken millions. He pointed to the same gap as increasingly characteristic across the globe, notably in the United States, where, as in India, enormous wealth now belongs to only a tiny sliver of the population as a whole. India ranks 5th for its number of billionaires (55 currently) while 860 million people barely survive on 50 cents a day. In one ironic aside, Sainath observed that while India sends its billionaires to Parliament, Russia sends hers to prison.

Yet a virtually criminal manipulation of facts and data consistently glosses over the reality of extreme poverty. Not only is there a major disconnect between what is deemed newsworthy and the plight of the vast majority of Indians, but even words and their re- definition have become tools of official policy.

- A few years ago, the province of Maharashtra legally “abolished” the word famine, rendering its use in official documents literally illegal.

- The 83 million tons of “surplus” grain in India turns out upon closer inspection to consist of grain that is beyond the purchasing power of those most in need of it. Rather than distribute it for free to starving people, the government designates it for export, but what is not actually shipped is left to rot in the fields.

Illustrating his contention that the “large canvas” global issue of our time is inequality, Sainath pointed to published annual statistics by the United Nations on how much could be done to address the issues of world hunger and sanitation with additional expenditure of only some $60 to $80 billion, yet lack of awareness and the absence of political will, allied with fierce dedication to stock market profitability, keep such investment permanently off the global agenda. Yet, in 2008, $32 billion was “grown overnight” by the US government to address the subprime mortgage crisis. This is a snapshot of what kind of a world we live in.

Eleven countries suffered especially calamitous devastation from the tsunami of 2004: yet of these, the five countries that had stock markets all hit historic highs within days after the tsunami struck. In the same week as 30,000 homes in Tamil Nadu were demolished by natural disaster, 48,000 homes in the slums of Mumbai were demolished by order of the government, a move met with widespread popular approval and encouraged by the mainstream media which praised “the destruction of this eyesore.”

Good journalism is to be judged by whether and how it addresses the major issues of the day. Sainath devotes his journalistic efforts to exposing the gross inequities that disfigure the “official” face of India; the ravages of agrarian policy for example are both the direct consequence of human intentionality and a damning indictment of India’s extreme inequality. Crime Records data, published annually and open for all to read, reveal the misery of the rural poor. 271, 000 Indian farmers have committed suicide (suicide is officially designated a crime) over the last 16 years, while the rate has so accelerated in the last 8 that there is now a suicide every 30 minutes. Pathetically, the suicide notes left by these “criminals” are addressed, not to their loved ones, but to finance ministers and banks, begging them to stop harassing farmers to pay up on their “debts,” debts driven brutally high by the application of exorbitant interest rates on loans. While a millionaire can obtain a 7% rate of interest for purchase of a Mercedes Benz, a rural farmer may be charged 14% on a loan to buy a tractor.

A lively question and answer session followed P. Sainath’s riveting account.

Respectfully submitted,

Joan E. Fleming