September 6, 2023

American Midnight: The Great War, a Violent Peace,

and Democracy’s Forgotten Crisis

Adam Hochschild

University of California Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism

American Midnight: The Great War, a Violent Peace,

and Democracy’s Forgotten Crisis

Adam Hochschild

University of California Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism

Minutes of the First Meeting of the 82nd Year

The minutes of the May 17th meeting were read by Rainer Muser.

A moment of silence was observed for three members who had passed since our last meeting: Carl Cangelosi, John Chatham, and John Lasley.

John Cotton called the First Meeting of the Old Guard’s 82nd year to order at 701 Carnegie Center. There were 120 members and guests in attendance.

The following members introduced candidates for membership:

1. Tom Pyle, introduced by Bill Katen-Narvell

2. Norm Klath by Rob Fraser

3. John Guthrie by David Scott

4. Margaret Miller by George Bustin

All other guests were asked to stand and be recognized as a group.

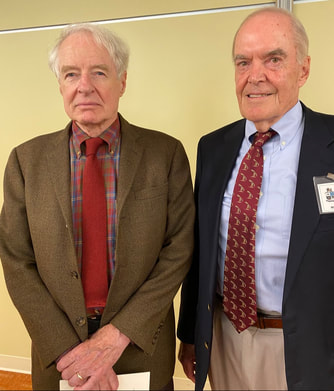

Michael Mathews introduced Adam Hochschild, Continuing Lecturer at the University of California at Berkeley School of Journalism and author of the new book “American Midnight: The Great War, a Violent Peace, and Democracy’s Forgotten Crisis.”

Hochschild grew up in Princeton, attended Miss Mason’s school, then Harvard, class of 1963. Among the speaker’s many awards and accomplishments was that of a finalist for the National Book Award. He was a reporter for the San Francisco Chronicle, a commentator on NPR’s “All Things Considered” and was the co-founder and editor of Mother Johes magazine. He is a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

The speaker began by describing a forgotten chapter in American History. While World War I captured the headlines and history books, the period running up to the war, Prohibition and the early Roaring 20’s were, in fact, tumultuous years. Major conflicts erupted between business and labor, nativists and immigrants, and Blacks and whites.

As examples, the speaker told us that dozens of pro-union miners in Butte, Montana, were killed in a confrontation with company police. In Edison Park, Chicago, German-authored books were burned. Towns such a Berlin, Iowa, adopted English names, and is now Lincoln, Iowa. North Dakota banned the speaking of German.

Lynchings were frequent, and not necessarily all in the south. In the single year 1919, there were 70 lynchings of African Americans. And the white mayor of Omaha, Nebraska, who came to the aid of a lynching victim, was himself strung up, but ultimately rescued.

Resistance to the war was significant, and often turbulent, led by a magazine called The Masses, which was a precursor to The New Yorker. Eugene Debs, who as a Socialist had garnered six percent of the vote in the 1912 presidential election, was imprisoned for his writings and speeches. Emma Goldman went to prison for protesting against the draft.

Robert LaFollette, a firebrand Wisconsin senator, stoked anti-immigrant feelings against many groups, including Irish, Egyptians, and East Indians. Vigilantes from groups such as the American Protective League and the Department of Justice Auxiliary hunted down and tarred and feathered persons who resisted the draft or refused to buy war bonds, so-called “Wobblies.”

The war was an excellent excuse to crack down on unions, foreigners, and racial troublemakers, about which President Woodrow Wilson had nothing much to say. The powers of the time equated the union movement to the Russian Bolsheviks.

As an example of blatant censorship, the speaker told of a largely unremembered but very powerful civil servant, Postmaster General Albert Burleson, who used his power to arbitrarily ban publications from being distributed through the mail, which was the only means of national distribution at the time. Burleson, a former Texas congressman from a slave-holding family, banned 400 publications from the mails, of which at least 75 were put out of business.

Labor organizer Eugene Debs, who, in his lifetime ran five times for president on the Socialist Party ticket, once from a jail cell setting an interesting precedent for the modern day. Emma Goldman was jailed and then deported for her anti-war activity along with 248 others. In Elaine, Arkansas, there was a single-event massacre of hundreds of black sharecroppers and union supporters.

But by 1921, there was pushback. Lewis Post, acting Secretary of Labor who ran the immigration bureau, granted amnesties, which infuriated a young FBI agent, J. Edgar Hoover. President Harding welcomed Eugene Debs to the White House in 1921 after he was let out of prison. The nation welcomed the amnesties. They were OK according to the author because “Wilson’s dirty work” had been completed.

The American Midnight had passed.

Yet speaking to us 100 years later, the speaker seemed to be asking, “had it really?”

Respectfully submitted,

Owen Leach

A moment of silence was observed for three members who had passed since our last meeting: Carl Cangelosi, John Chatham, and John Lasley.

John Cotton called the First Meeting of the Old Guard’s 82nd year to order at 701 Carnegie Center. There were 120 members and guests in attendance.

The following members introduced candidates for membership:

1. Tom Pyle, introduced by Bill Katen-Narvell

2. Norm Klath by Rob Fraser

3. John Guthrie by David Scott

4. Margaret Miller by George Bustin

All other guests were asked to stand and be recognized as a group.

Michael Mathews introduced Adam Hochschild, Continuing Lecturer at the University of California at Berkeley School of Journalism and author of the new book “American Midnight: The Great War, a Violent Peace, and Democracy’s Forgotten Crisis.”

Hochschild grew up in Princeton, attended Miss Mason’s school, then Harvard, class of 1963. Among the speaker’s many awards and accomplishments was that of a finalist for the National Book Award. He was a reporter for the San Francisco Chronicle, a commentator on NPR’s “All Things Considered” and was the co-founder and editor of Mother Johes magazine. He is a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

The speaker began by describing a forgotten chapter in American History. While World War I captured the headlines and history books, the period running up to the war, Prohibition and the early Roaring 20’s were, in fact, tumultuous years. Major conflicts erupted between business and labor, nativists and immigrants, and Blacks and whites.

As examples, the speaker told us that dozens of pro-union miners in Butte, Montana, were killed in a confrontation with company police. In Edison Park, Chicago, German-authored books were burned. Towns such a Berlin, Iowa, adopted English names, and is now Lincoln, Iowa. North Dakota banned the speaking of German.

Lynchings were frequent, and not necessarily all in the south. In the single year 1919, there were 70 lynchings of African Americans. And the white mayor of Omaha, Nebraska, who came to the aid of a lynching victim, was himself strung up, but ultimately rescued.

Resistance to the war was significant, and often turbulent, led by a magazine called The Masses, which was a precursor to The New Yorker. Eugene Debs, who as a Socialist had garnered six percent of the vote in the 1912 presidential election, was imprisoned for his writings and speeches. Emma Goldman went to prison for protesting against the draft.

Robert LaFollette, a firebrand Wisconsin senator, stoked anti-immigrant feelings against many groups, including Irish, Egyptians, and East Indians. Vigilantes from groups such as the American Protective League and the Department of Justice Auxiliary hunted down and tarred and feathered persons who resisted the draft or refused to buy war bonds, so-called “Wobblies.”

The war was an excellent excuse to crack down on unions, foreigners, and racial troublemakers, about which President Woodrow Wilson had nothing much to say. The powers of the time equated the union movement to the Russian Bolsheviks.

As an example of blatant censorship, the speaker told of a largely unremembered but very powerful civil servant, Postmaster General Albert Burleson, who used his power to arbitrarily ban publications from being distributed through the mail, which was the only means of national distribution at the time. Burleson, a former Texas congressman from a slave-holding family, banned 400 publications from the mails, of which at least 75 were put out of business.

Labor organizer Eugene Debs, who, in his lifetime ran five times for president on the Socialist Party ticket, once from a jail cell setting an interesting precedent for the modern day. Emma Goldman was jailed and then deported for her anti-war activity along with 248 others. In Elaine, Arkansas, there was a single-event massacre of hundreds of black sharecroppers and union supporters.

But by 1921, there was pushback. Lewis Post, acting Secretary of Labor who ran the immigration bureau, granted amnesties, which infuriated a young FBI agent, J. Edgar Hoover. President Harding welcomed Eugene Debs to the White House in 1921 after he was let out of prison. The nation welcomed the amnesties. They were OK according to the author because “Wilson’s dirty work” had been completed.

The American Midnight had passed.

Yet speaking to us 100 years later, the speaker seemed to be asking, “had it really?”

Respectfully submitted,

Owen Leach