November 15, 2023

Road To Surrender

Evan and Oscie Thomas

Author, Journalist; Former Ferris Professor of Journalism, Princeton University

Road To Surrender

Evan and Oscie Thomas

Author, Journalist; Former Ferris Professor of Journalism, Princeton University

Minutes of the 11th Meeting of the 82nd Year

President John Cotton called the meeting to order and presided. Frances Slade led the invocation, and Ralph Widner read the minutes of the prior meeting. The attendance was a large 135. There were several guests: Audrey Egger (guest of David Egger). Sarah Jones (guest of Lanny Jones), Paul Miles (guest of Evan Thomas), Pam Wakefield (guest of Bill Wakefield), and Walter Wentz (guest of Henry Van Kohorn). John Cotton requested a moment of silence in remembrance of the passing of Jared Fowler on November 7, 2023.

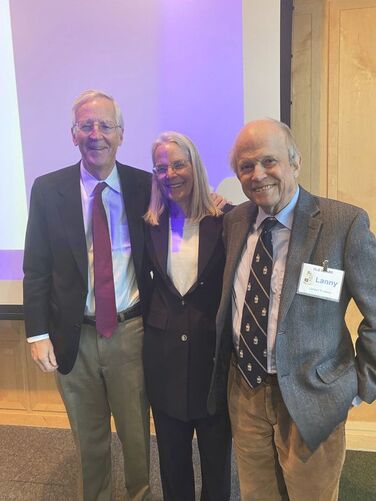

Lanny Jones introduced the speakers, Evan and Oscie Thomas, well-known journalists for publications such as Time and Newsweek, and historians and authors. Oscie is also a lawyer. Evan was the resident Ferris Professor of Journalism at Princeton in 2007-2014. The Thomases employed a conversational question-and-answer format for the discussion to good effect.

The talk comprised the content of Evan’s 2023 book Road to Surrender, which describes the men and decisions that led to the U.S. deployment of two atomic bombs on Japan to end World War II. Evan Thomas was interested in this topic because it continues to be controversial, as well as being timely with the recent movie Oppenheimer, released in summer 2023. Did the U.S. need to drop an atomic bomb to end the war? Did the U.S. need to drop two bombs? Were the Japanese not already on the verge of surrendering without such a display of Allied might?

The focus was on three main characters during the war who are not particularly familiar to the public. All three had written extensive diaries. The first was Harold Stimson, U.S. Secretary of War, ailing with heart problems. He was a highly moral man who worried about bombing civilians and refused to allow the ancient and former Japanese capital city of Kyoto to be listed as a possible bombing target. The second was General Carl Spaatz, U.S. Army Air Forces head of strategic bombing in the Pacific, who ably managed the crews that dropped the two bombs on August 6 and 9, 1945, and prepared for more, if Japan did not surrender. He intensely disliked killing civilians but followed orders as a good soldier.

The third character was Shigenori Togo, Japanese foreign minister. He was the only member of Emperor Hirohito’s six-member Supreme War Council who believed that Japan should surrender, even before the bombs were dropped. Togo was a unique senior bureaucrat who spoke bluntly, not in the passive indirect manner of most educated Japanese. He came up through the diplomatic ranks, had many international postings in the West, including serving in the Embassy of Japan in the United States in Washington DC during the 1920s.

The interplay between Togo, the Japanese War Minister General Korechika Anami and Emperor Hirohito was intricately discussed. It was surprising to learn that many of the senior government ministers were afraid of their Japanese soldiers. They feared that they would be killed if they proposed surrender. But Togo allied himself with the emperor, who did want to surrender, and eventually, after the second bomb dropped on Nagasaki on August 9, active discussions of surrender ensued. The major sticking point during final negotiations was the role of the emperor. Japan demanded that the emperor remain. The U.S. agreed eventually, but that he be subject to the Supreme Allied Commander, U.S. General Douglas MacArthur.

In the end, Japan’s decision to surrender saved many Japanese lives, because the civilian population was on the verge of starvation, as were huge swaths in Asia. It also saved untold numbers of American lives who did not need to participate in the planned land invasions of the home islands Kyushu and Honshu, which would have involved extremely intense fighting.

Respectfully submitted,

Julianne Elward-Berry

Lanny Jones introduced the speakers, Evan and Oscie Thomas, well-known journalists for publications such as Time and Newsweek, and historians and authors. Oscie is also a lawyer. Evan was the resident Ferris Professor of Journalism at Princeton in 2007-2014. The Thomases employed a conversational question-and-answer format for the discussion to good effect.

The talk comprised the content of Evan’s 2023 book Road to Surrender, which describes the men and decisions that led to the U.S. deployment of two atomic bombs on Japan to end World War II. Evan Thomas was interested in this topic because it continues to be controversial, as well as being timely with the recent movie Oppenheimer, released in summer 2023. Did the U.S. need to drop an atomic bomb to end the war? Did the U.S. need to drop two bombs? Were the Japanese not already on the verge of surrendering without such a display of Allied might?

The focus was on three main characters during the war who are not particularly familiar to the public. All three had written extensive diaries. The first was Harold Stimson, U.S. Secretary of War, ailing with heart problems. He was a highly moral man who worried about bombing civilians and refused to allow the ancient and former Japanese capital city of Kyoto to be listed as a possible bombing target. The second was General Carl Spaatz, U.S. Army Air Forces head of strategic bombing in the Pacific, who ably managed the crews that dropped the two bombs on August 6 and 9, 1945, and prepared for more, if Japan did not surrender. He intensely disliked killing civilians but followed orders as a good soldier.

The third character was Shigenori Togo, Japanese foreign minister. He was the only member of Emperor Hirohito’s six-member Supreme War Council who believed that Japan should surrender, even before the bombs were dropped. Togo was a unique senior bureaucrat who spoke bluntly, not in the passive indirect manner of most educated Japanese. He came up through the diplomatic ranks, had many international postings in the West, including serving in the Embassy of Japan in the United States in Washington DC during the 1920s.

The interplay between Togo, the Japanese War Minister General Korechika Anami and Emperor Hirohito was intricately discussed. It was surprising to learn that many of the senior government ministers were afraid of their Japanese soldiers. They feared that they would be killed if they proposed surrender. But Togo allied himself with the emperor, who did want to surrender, and eventually, after the second bomb dropped on Nagasaki on August 9, active discussions of surrender ensued. The major sticking point during final negotiations was the role of the emperor. Japan demanded that the emperor remain. The U.S. agreed eventually, but that he be subject to the Supreme Allied Commander, U.S. General Douglas MacArthur.

In the end, Japan’s decision to surrender saved many Japanese lives, because the civilian population was on the verge of starvation, as were huge swaths in Asia. It also saved untold numbers of American lives who did not need to participate in the planned land invasions of the home islands Kyushu and Honshu, which would have involved extremely intense fighting.

Respectfully submitted,

Julianne Elward-Berry