March 1, 2023

Some Lessons from American Monetary and Fiscal Policy

Alan Blinder

Former Vice Chair, Federal Reserve;

Professor of Economics and Public Affairs, Princeton University

Minutes of the 21th Meeting of the 81st Year

President John Cotton convened the meeting. Marsha Levin-Rojer read the minutes for the previous meeting. One hundred twenty-three attended this first in-person meeting for 2023. BF Graham introduced his guest, Paul Fitzgerald, who is a nominee for membership. Sarah Ringer introduced her guest, Steve Silverman. John Fleming introduced his guest, his wife, Joan. Tony Glockler introduced his guest, his wife Bev. Archer Harvey introduced Lynn Johnston, his nominee for membership. Marcia Snowden introduced her guest, George Harvey.

President John Cotton requested a moment of silence in remembrance of longtime member Robert Geddes, distinguished architect and former Dean of Princeton University’s School of Architecture.

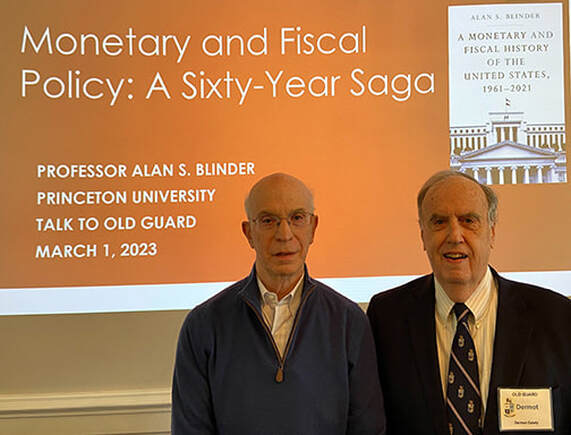

Dermot Gately introduced the speaker, Alan S. Blinder, Professor of Economics and Public Affairs at Princeton University, who served as a member of the Council of Economic Advisors in the Clinton Administration, then as vice chair of the Federal Reserve. Drawing from his book published last year on the topic, Professor Blinder summarized the ups and downs of U.S. monetary and fiscal policy during the tumultuous years from 1961 to 2021.

In the 1960s, the Kennedy administration for the first time, introduced Keynesian economics into formulation of U.S. economic policy. Properly implemented, the approach calls for Congress and the administration’s fiscal policies of taxing and spending to row in tandem with the monetary policies of the Federal Reserve as it manages the supply and cost of money. However, over the course of the sixty years—with some notable exceptions—the rowers often paddled in opposite directions. Questions arose about who plays first violin and who plays second fiddle. And attitudes regarding budget deficits and the independence of the Federal Reserve itself changed as well.

In the sixties, despite inheriting a large budget deficit and a sluggish, though recovering economy, President Kennedy proposed a large tax cut, unenacted until after his assassination and Lyndon Johnson became president. In 1968, the Economic Report of the President quite remarkably stated that “It has been and remains the conviction of both the administration and the Federal Reserve system that the nation should depend on fiscal policy, not monetary policy, to carry the main burden of the additional restraint on the growth of demand that now appears necessary for 1968.” Johnson actually asked his Attorney General if he could fire Federal Reserve chair William McChesney Martin and was told he couldn’t. However, Johnson’s “guns and butter” spending for Great Society programs and the costs of the Vietnam War generated excessive demand in the economy. He was compelled to ask for tax increases to cover them and to dampen the overheated economy—the last time that fiscal policies alone were used to do so.

Richard Nixon inherited this inflationary economy and appointed a friend, Arthur Burns, as chair of the Federal Reserve, who cooperated in implementing highly expansionary fiscal and monetary policies during a period of supply shocks. This sparked inflation. Nixon resorted at first to price controls, but, as they were lifted, double-digit inflation combined with rising unemployment ensued —“stagflation”— something that is not supposed to happen. Policy-making confusion ensued. When Gerald Ford took over after Nixon resigned, he first asked for a tax hike in October 1974, then a tax cut in January 1975. The Federal Reserve’s monetary policies under Arthur Burns also vacillated.

Enter Jimmy Carter, the bad-luck president. Carter hated deficits, so was unwilling to provide more than a mild stimulus in 1977, while the new chair of the Federal Reserve appeared to be really soft on inflation, raising interest rates by only 450 basis points. Then, OPEC greatly constrained oil supplies to drive up the price of oil. With inflation at unacceptably high levels, Carter took a step guaranteed to doom his presidency—he appointed Paul Volcker as chair of the Federal Reserve and gave him full rein to bring inflation under control. Converted to “monetarism,” and with full independence, Volcker raised interest rates to levels that cratered the economy, but eventually broke the spiral of inflation.

As inflation was coming down, Ronald Reagan was elected. Unemployment remained high, so despite the tight money policies at the Federal Reserve, Reagan loosened fiscal policy and Congress cooperated by enacting tax cuts in 1982. So the economic slump was followed by a “morning in America” boom. However, with sky-high real interest rates and a soaring dollar, American manufacturing dispersed to low-cost areas around the country and around the world, decimating American manufacturing, creating the “Rust Belt,” and leaving a legacy of chronic, large fiscal deficits.

When George H.W. Bush entered office the legacy of Reagan’s deficits crowded out any thought of using fiscal stimuli, despite a recession in 1990-1991. Soon fiscal policy focused solely upon reducing the deficit, while the Federal Reserve maintained a tight money policy—about as anti-Keynesian as you can get.

Clinton came in sharing this same determination to reduce the deficit but was equally determined not to interfere with the independence of the Federal Reserve. However, the Fed did reduce interest rates and a bond rally ensued. The economy recovered and Clinton left a legacy of large budget surpluses, the only one among presidents who served during these sixty years to do so.

However, with the election of George W. Bush, that legacy was quickly erased. Vice President Cheney asserted that Reagan had proved “that deficits don’t matter.” The administration and Congress abolished the PAYGO procedure which required that financing for any new initiatives had to be identified before they were adopted. Surpluses turned back into deficits very quickly. Then, the collapse of Lehmann Brothers triggered a major global economic crisis driving the economy into the worst recession since the 1930s. The Federal Reserve dropped interest rates to zero. For the first time in decades, neither fiscal nor monetary policy alone was enough. They needed to be orchestrated in concert.

This was the situation inherited by the incoming Obama administration, which pressed through a “Recovery Act” stimulus criticized by opponents as “massive” and “job-killing,” but which proved too small. After 2010, fiscal policy turned contractionary, but the Federal Reserve, under Ben Bernanke, purposely maintained expansionary monetary policies that moved the country back into full employment.

Despite that, in the first year of the Trump administration, it instituted a large tax cut. Then, when the Covid pandemic struck, Trump supported Congress’ gigantic fiscal stimulus, the CARES Act and the Federal Reserve threw the kitchen sink at the recession. This time, both fiscal and monetary policies were working together to abbreviate any recession triggered by lockdowns.

In March 2021, the Biden administration succeeded in getting Congress to inject still more stimulus into the Covid economy with the American Rescue Plan, criticized at the time and since as too large. Notably, the Fed did not try to offset it with tighter money until a year later, recognizing that excess fiscal stimulus, combined with other geopolitical developments, had sparked a rise in inflation to unacceptably high levels. Notably, Biden continued Clinton’s “hands off the Fed” policy. That is where we are today, relying much more heavily upon monetary policies of the Fed than at the beginning of the six decades; coupled with declining concern about deficits than at the start; and rising support for the independence of the Federal Reserve.

Respectfully submitted,

Ralph R. Widner

President John Cotton requested a moment of silence in remembrance of longtime member Robert Geddes, distinguished architect and former Dean of Princeton University’s School of Architecture.

Dermot Gately introduced the speaker, Alan S. Blinder, Professor of Economics and Public Affairs at Princeton University, who served as a member of the Council of Economic Advisors in the Clinton Administration, then as vice chair of the Federal Reserve. Drawing from his book published last year on the topic, Professor Blinder summarized the ups and downs of U.S. monetary and fiscal policy during the tumultuous years from 1961 to 2021.

In the 1960s, the Kennedy administration for the first time, introduced Keynesian economics into formulation of U.S. economic policy. Properly implemented, the approach calls for Congress and the administration’s fiscal policies of taxing and spending to row in tandem with the monetary policies of the Federal Reserve as it manages the supply and cost of money. However, over the course of the sixty years—with some notable exceptions—the rowers often paddled in opposite directions. Questions arose about who plays first violin and who plays second fiddle. And attitudes regarding budget deficits and the independence of the Federal Reserve itself changed as well.

In the sixties, despite inheriting a large budget deficit and a sluggish, though recovering economy, President Kennedy proposed a large tax cut, unenacted until after his assassination and Lyndon Johnson became president. In 1968, the Economic Report of the President quite remarkably stated that “It has been and remains the conviction of both the administration and the Federal Reserve system that the nation should depend on fiscal policy, not monetary policy, to carry the main burden of the additional restraint on the growth of demand that now appears necessary for 1968.” Johnson actually asked his Attorney General if he could fire Federal Reserve chair William McChesney Martin and was told he couldn’t. However, Johnson’s “guns and butter” spending for Great Society programs and the costs of the Vietnam War generated excessive demand in the economy. He was compelled to ask for tax increases to cover them and to dampen the overheated economy—the last time that fiscal policies alone were used to do so.

Richard Nixon inherited this inflationary economy and appointed a friend, Arthur Burns, as chair of the Federal Reserve, who cooperated in implementing highly expansionary fiscal and monetary policies during a period of supply shocks. This sparked inflation. Nixon resorted at first to price controls, but, as they were lifted, double-digit inflation combined with rising unemployment ensued —“stagflation”— something that is not supposed to happen. Policy-making confusion ensued. When Gerald Ford took over after Nixon resigned, he first asked for a tax hike in October 1974, then a tax cut in January 1975. The Federal Reserve’s monetary policies under Arthur Burns also vacillated.

Enter Jimmy Carter, the bad-luck president. Carter hated deficits, so was unwilling to provide more than a mild stimulus in 1977, while the new chair of the Federal Reserve appeared to be really soft on inflation, raising interest rates by only 450 basis points. Then, OPEC greatly constrained oil supplies to drive up the price of oil. With inflation at unacceptably high levels, Carter took a step guaranteed to doom his presidency—he appointed Paul Volcker as chair of the Federal Reserve and gave him full rein to bring inflation under control. Converted to “monetarism,” and with full independence, Volcker raised interest rates to levels that cratered the economy, but eventually broke the spiral of inflation.

As inflation was coming down, Ronald Reagan was elected. Unemployment remained high, so despite the tight money policies at the Federal Reserve, Reagan loosened fiscal policy and Congress cooperated by enacting tax cuts in 1982. So the economic slump was followed by a “morning in America” boom. However, with sky-high real interest rates and a soaring dollar, American manufacturing dispersed to low-cost areas around the country and around the world, decimating American manufacturing, creating the “Rust Belt,” and leaving a legacy of chronic, large fiscal deficits.

When George H.W. Bush entered office the legacy of Reagan’s deficits crowded out any thought of using fiscal stimuli, despite a recession in 1990-1991. Soon fiscal policy focused solely upon reducing the deficit, while the Federal Reserve maintained a tight money policy—about as anti-Keynesian as you can get.

Clinton came in sharing this same determination to reduce the deficit but was equally determined not to interfere with the independence of the Federal Reserve. However, the Fed did reduce interest rates and a bond rally ensued. The economy recovered and Clinton left a legacy of large budget surpluses, the only one among presidents who served during these sixty years to do so.

However, with the election of George W. Bush, that legacy was quickly erased. Vice President Cheney asserted that Reagan had proved “that deficits don’t matter.” The administration and Congress abolished the PAYGO procedure which required that financing for any new initiatives had to be identified before they were adopted. Surpluses turned back into deficits very quickly. Then, the collapse of Lehmann Brothers triggered a major global economic crisis driving the economy into the worst recession since the 1930s. The Federal Reserve dropped interest rates to zero. For the first time in decades, neither fiscal nor monetary policy alone was enough. They needed to be orchestrated in concert.

This was the situation inherited by the incoming Obama administration, which pressed through a “Recovery Act” stimulus criticized by opponents as “massive” and “job-killing,” but which proved too small. After 2010, fiscal policy turned contractionary, but the Federal Reserve, under Ben Bernanke, purposely maintained expansionary monetary policies that moved the country back into full employment.

Despite that, in the first year of the Trump administration, it instituted a large tax cut. Then, when the Covid pandemic struck, Trump supported Congress’ gigantic fiscal stimulus, the CARES Act and the Federal Reserve threw the kitchen sink at the recession. This time, both fiscal and monetary policies were working together to abbreviate any recession triggered by lockdowns.

In March 2021, the Biden administration succeeded in getting Congress to inject still more stimulus into the Covid economy with the American Rescue Plan, criticized at the time and since as too large. Notably, the Fed did not try to offset it with tighter money until a year later, recognizing that excess fiscal stimulus, combined with other geopolitical developments, had sparked a rise in inflation to unacceptably high levels. Notably, Biden continued Clinton’s “hands off the Fed” policy. That is where we are today, relying much more heavily upon monetary policies of the Fed than at the beginning of the six decades; coupled with declining concern about deficits than at the start; and rising support for the independence of the Federal Reserve.

Respectfully submitted,

Ralph R. Widner