April 3, 2013

The Frontiers and Limits of Science

Robbert Dijkgraaf

Director, Institute for Advanced Study

The Frontiers and Limits of Science

Robbert Dijkgraaf

Director, Institute for Advanced Study

Minutes of the 24th Meeting of the 71st Year

Two weeks ago (March 27, 2013) we heard Shirley Tilghman tell us that one of the challenges facing the next president of Princeton University is the decline in government funds for scientific research. Last week (April 3, 2013) we heard Robbert Dijkraaf (pronounced Die-graph) give an eloquent and entertaining talk on the value of that same research that is in financial jeopardy.

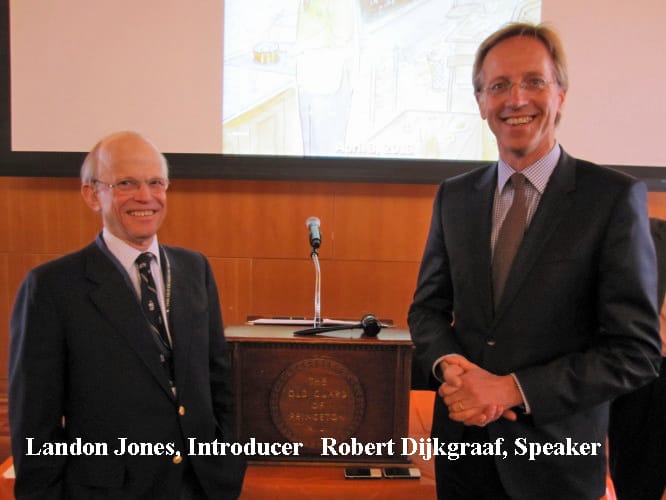

Landon Jones introduced the speaker as a scientist, scholar, and educator of astonishing breadth and depth. As a mathematical physicist he has made an impact on string theory. As an educator he has developed a science web site for children and is a professor at the University of Amsterdam. A native of the Netherlands, he grew up in the suburbs of Rotterdam and received his undergraduate and graduate degrees in theoretical physics at Utrecht University. He is in his ninth month as the ninth Director of the Institute for Advanced Study.

It’s not often you hear the Duke of Wellington or Donald Rumsfeld quoted in a lecture on scientific research. Wellington said, “the business of life is to endeavour to find out what you don't know by what you do know; that's what I called ‘guessing what was at the other side of the hill’." Rumsfeld famously referred to ‘unknown unknowns”.

An example of genius in looking beyond what we know is William Hershel. He looked over the rainbow and found the invisible infrared beyond the visible red.

Recent work in cosmology has shown that 96% of the universe is dark energy or dark matter. These terms are really euphemisms for what we now know we don’t know. Twenty years ago they were the Rumsfeldian “unknown unknowns.”

Dijkraaf reminded us that other fields of research also have limitations on what is available for study. Perhaps 5% of Greek plays have survived; whole civilizations have left no trace for archeologists; and only a small percentage of prehistoric organisms have left a fossil record. Before much of the geography of the world became known, map makers filled in the areas of the unknown land and sea with monsters and other imaginary creatures, a visible manifestation of what Dijkraaf called “dark knowledge.”

Our speaker also referred to what Abraham Flexner, the first director of the Institute for Advanced Study, called “the usefulness of useless knowledge.” Flexner advised the philanthropists who funded the Institute that there was a need to support ‘blue sky’ research.

It was ‘useless’ curiosity that motivated Faraday’s experiments with electricity. Today the world literally stops when there is a black out. However, the New York Times reviewed the first electric light bulb as a curiosity saying it was like the gas light, only it didn’t smell.

Superconductivity was a curiosity in 1911. Today it is used in the superconducting magnets that let MRI scans find defects in our bodies and the CERN Large Hadron Collider detect the Higgs boson.

The results of “useless” quantum mechanics are behind the lasers and transistors that power fifty percent of present industry. (And, I would add, behind the cell phones that may interrupt an Old Guard lecture.)

Dijkraaf then turned our attention from the borders of the unknown to the borders between the fields of science. The proliferation of different fields of research is building too many internal walls that divide the unity of knowledge.

Other borders are the physical borders in the world community. Scientific output is far from equal among nations. However, there is strong collaboration among individual scientists in the leading countries. Only five of the twenty-seven members of the permanent faculty at the Institute were born in the United States. Thirty percent of the members of the U.S. Academy of Science were not born in the U.S.

Dijkraaf concluded his talk with comments on the public role of science. The borders between the scientific area, academia, and the world outside are changing. As science digs deeper in a subject it becomes more difficult to understand and yet the impact of science on the individual becomes bigger and bigger. For example, we now understand the human body on a molecular level and that means we can target a drug for a specific individual.

It’s difficult to communicate science to the public because science is complicated and hard to simplify. In a pro and con discussion on television between a scientist and an activist with an agenda, the scientist is at a disadvantage because the activist isn’t always encumbered by facts.

The morning ended with Dijkraff’s agreeing with a question about the public’s lack of respect for scientific expertise. This observer wonders if we haven’t come full circle back to one reason for the decline of funding mentioned by President Tilghman.

The meeting at the Fields Center on the Princeton University Campus began at 9:30 a.m. with a social time for conversation and refreshments. President Ruth Miller called the formal meeting to order at 10:15 a.m. Don Edwards led the invocation and Owen Leach read his minutes of the meeting on March 27, 2013.

Several members introduced guests. Bill Strong – his friend Bob Fleming; Bill Bolger – his sister Betty Fleming; Charlie Stenard – his wife Liz Stenard; David Scott – his wife Ruth Scott; Alison Lahnston – her friend Helen –Keith Smeltzer; and Michael Kaplan – his friend Jon Van Raalte.

Membership Chair Jack Reilly announced that Carl Brown was now an emeritus member.

The meeting was adjourned at 11:30 a.m.

The total attendance was 130 – a new record.

Respectfully submitted,

Jock McFarlane

Landon Jones introduced the speaker as a scientist, scholar, and educator of astonishing breadth and depth. As a mathematical physicist he has made an impact on string theory. As an educator he has developed a science web site for children and is a professor at the University of Amsterdam. A native of the Netherlands, he grew up in the suburbs of Rotterdam and received his undergraduate and graduate degrees in theoretical physics at Utrecht University. He is in his ninth month as the ninth Director of the Institute for Advanced Study.

It’s not often you hear the Duke of Wellington or Donald Rumsfeld quoted in a lecture on scientific research. Wellington said, “the business of life is to endeavour to find out what you don't know by what you do know; that's what I called ‘guessing what was at the other side of the hill’." Rumsfeld famously referred to ‘unknown unknowns”.

An example of genius in looking beyond what we know is William Hershel. He looked over the rainbow and found the invisible infrared beyond the visible red.

Recent work in cosmology has shown that 96% of the universe is dark energy or dark matter. These terms are really euphemisms for what we now know we don’t know. Twenty years ago they were the Rumsfeldian “unknown unknowns.”

Dijkraaf reminded us that other fields of research also have limitations on what is available for study. Perhaps 5% of Greek plays have survived; whole civilizations have left no trace for archeologists; and only a small percentage of prehistoric organisms have left a fossil record. Before much of the geography of the world became known, map makers filled in the areas of the unknown land and sea with monsters and other imaginary creatures, a visible manifestation of what Dijkraaf called “dark knowledge.”

Our speaker also referred to what Abraham Flexner, the first director of the Institute for Advanced Study, called “the usefulness of useless knowledge.” Flexner advised the philanthropists who funded the Institute that there was a need to support ‘blue sky’ research.

It was ‘useless’ curiosity that motivated Faraday’s experiments with electricity. Today the world literally stops when there is a black out. However, the New York Times reviewed the first electric light bulb as a curiosity saying it was like the gas light, only it didn’t smell.

Superconductivity was a curiosity in 1911. Today it is used in the superconducting magnets that let MRI scans find defects in our bodies and the CERN Large Hadron Collider detect the Higgs boson.

The results of “useless” quantum mechanics are behind the lasers and transistors that power fifty percent of present industry. (And, I would add, behind the cell phones that may interrupt an Old Guard lecture.)

Dijkraaf then turned our attention from the borders of the unknown to the borders between the fields of science. The proliferation of different fields of research is building too many internal walls that divide the unity of knowledge.

Other borders are the physical borders in the world community. Scientific output is far from equal among nations. However, there is strong collaboration among individual scientists in the leading countries. Only five of the twenty-seven members of the permanent faculty at the Institute were born in the United States. Thirty percent of the members of the U.S. Academy of Science were not born in the U.S.

Dijkraaf concluded his talk with comments on the public role of science. The borders between the scientific area, academia, and the world outside are changing. As science digs deeper in a subject it becomes more difficult to understand and yet the impact of science on the individual becomes bigger and bigger. For example, we now understand the human body on a molecular level and that means we can target a drug for a specific individual.

It’s difficult to communicate science to the public because science is complicated and hard to simplify. In a pro and con discussion on television between a scientist and an activist with an agenda, the scientist is at a disadvantage because the activist isn’t always encumbered by facts.

The morning ended with Dijkraff’s agreeing with a question about the public’s lack of respect for scientific expertise. This observer wonders if we haven’t come full circle back to one reason for the decline of funding mentioned by President Tilghman.

The meeting at the Fields Center on the Princeton University Campus began at 9:30 a.m. with a social time for conversation and refreshments. President Ruth Miller called the formal meeting to order at 10:15 a.m. Don Edwards led the invocation and Owen Leach read his minutes of the meeting on March 27, 2013.

Several members introduced guests. Bill Strong – his friend Bob Fleming; Bill Bolger – his sister Betty Fleming; Charlie Stenard – his wife Liz Stenard; David Scott – his wife Ruth Scott; Alison Lahnston – her friend Helen –Keith Smeltzer; and Michael Kaplan – his friend Jon Van Raalte.

Membership Chair Jack Reilly announced that Carl Brown was now an emeritus member.

The meeting was adjourned at 11:30 a.m.

The total attendance was 130 – a new record.

Respectfully submitted,

Jock McFarlane