May 15, 2019

The Worlds of Frankenstein and Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde

Susan Wolfson

Professor of English, Princeton University

Minutes of the 31st Meeting of the 77th Year

The Old Guard met on May 15, 2019 at 10:15 a.m. in Meader Hall, the Andlinger Center. Julia Coale presided, Charlie Clark led the Invocation. Jeffrey Tener read the minutes for the preceding week, Jeffrey Tener had guests Barbara Clark and Terry Clark. Joan Fleming’s guest was John Fleming. Attendance was 93.

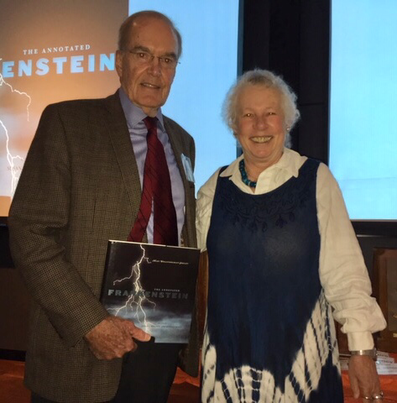

Michael Mathews introduced Susan Wolfson, Professor of English, Princeton University.

In Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus (1818), a man creates a monster, and, in Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1886), a man becomes a monster. Both Victor Frankenstein’s unnamed Creature and Dr. Jekyll’s metamorphic Mr. Hyde become murderous. At the catastrophic conclusions of these stories the scientist-creators are both dead, Frankenstein’s monster is dog-sledding off to his self-immolation, and Mr. Hyde dies simultaneously with Dr. Jekyll.

Narratively, each tale positions an important on-looker. Shelley includes Capt. Robert Walton, an ambitious explorer who learns the story from Frankenstein himself, while Stevenson uses Mr. Utterson, a respectably uptight lawyer-friend to find the dead Dr. Jekyll’s letter of confession.

Prof. Susan Wolfson calls these tales “origin stories.” On the one hand, both narrate the experimental origin of a living being: Victor Frankenstein’s eight-foot Creature and Dr. Jekyll’s sometime double. On the other hand, Prof. Wolfson emphasizes each story’s origin as a story, with particular emphasis on Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley’s inspiration for the enduringly popular (never out of print) Frankenstein.

Mary Shelley’s tale came out of a ghost-story competition: The other competitors, including the poets Byron and Shelley dropped out; but Mary finished and published her book anonymously in 1818. The public was horrified; one parliamentarian even cited the “spectacle of this creature (a giant of eight feet) and the threat it signified” in a speech warning against a too-rapid abolition of slavery. Reissues were published, now including her name, Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley or Mary W. Shelley, as well as an “Introduction” (1831) that answers the question “How I, then a young girl, came to think of, and to dilate upon, so very hideous an idea?” Here Shelley provides a two-fold origin for her tale. One is a nightmare she had about galvanism, the supposed means of resuscitating a dead body. The other is the encouragement of her husband, Percy Bysshe Shelley, who wants her to “prove myself worthy of my parentage, and enrol myself on the page of fame. He was for ever inciting me to obtain literary reputation (sic).”

That celebrity parentage, as Prof. Wolfson explains, included philosophical radicalism, sexual recklessness, and parental negligence. William Godwin, her father, was an anarchist philosopher and political novelist; Mary Wollstonecraft, her mother, was a champion of the French Revolution, a caustic feminist philosopher, and the unwed mother of Fanny Imlay (Mary’s half-sister, whose suicide coincided with the writing of Frankenstein). Relevant, too, is Mary’s own parenting tragedy, the death in less than a month of her firstborn child, an unnamed daughter (d. March 5. 1815). There are various other scandals, suicides, abandonments, and what Prof. Wolfson calls “faults of paternity” underlying Frankenstein. Victor Frankenstein, Prof. Wolfson says, “is all egotism, big on self-pity and wounded pride…. Failing to create a being whom he could bear (let alone love), Frankenstein recoils from a catastrophic wretch…. the Creature wakes into hell: reviled by his creator.”

Similar failure marks the end of Robert Louis Stevenson’s tale when Dr. Jekyll’s ambitious scientific plan derails disastrously. At the outset, however, and this is what Prof. Wolfson emphasizes, Dr. Jekyll is a ‘respectable gentleman’ who “in midlife crisis, wants to recover a youthful vitality long gone, and never fully enjoyed.” He is weary of the respectability he shares with “all of London’s drab professional men” including his friend Mr. Utterson. Prof. Wolfson takes this tale of Jekyll-Hyde doubleness to be a serious critique of 19th century culture: the code of respectability.

Respectfully submitted,

Constance W. Hassett

Michael Mathews introduced Susan Wolfson, Professor of English, Princeton University.

In Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus (1818), a man creates a monster, and, in Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1886), a man becomes a monster. Both Victor Frankenstein’s unnamed Creature and Dr. Jekyll’s metamorphic Mr. Hyde become murderous. At the catastrophic conclusions of these stories the scientist-creators are both dead, Frankenstein’s monster is dog-sledding off to his self-immolation, and Mr. Hyde dies simultaneously with Dr. Jekyll.

Narratively, each tale positions an important on-looker. Shelley includes Capt. Robert Walton, an ambitious explorer who learns the story from Frankenstein himself, while Stevenson uses Mr. Utterson, a respectably uptight lawyer-friend to find the dead Dr. Jekyll’s letter of confession.

Prof. Susan Wolfson calls these tales “origin stories.” On the one hand, both narrate the experimental origin of a living being: Victor Frankenstein’s eight-foot Creature and Dr. Jekyll’s sometime double. On the other hand, Prof. Wolfson emphasizes each story’s origin as a story, with particular emphasis on Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley’s inspiration for the enduringly popular (never out of print) Frankenstein.

Mary Shelley’s tale came out of a ghost-story competition: The other competitors, including the poets Byron and Shelley dropped out; but Mary finished and published her book anonymously in 1818. The public was horrified; one parliamentarian even cited the “spectacle of this creature (a giant of eight feet) and the threat it signified” in a speech warning against a too-rapid abolition of slavery. Reissues were published, now including her name, Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley or Mary W. Shelley, as well as an “Introduction” (1831) that answers the question “How I, then a young girl, came to think of, and to dilate upon, so very hideous an idea?” Here Shelley provides a two-fold origin for her tale. One is a nightmare she had about galvanism, the supposed means of resuscitating a dead body. The other is the encouragement of her husband, Percy Bysshe Shelley, who wants her to “prove myself worthy of my parentage, and enrol myself on the page of fame. He was for ever inciting me to obtain literary reputation (sic).”

That celebrity parentage, as Prof. Wolfson explains, included philosophical radicalism, sexual recklessness, and parental negligence. William Godwin, her father, was an anarchist philosopher and political novelist; Mary Wollstonecraft, her mother, was a champion of the French Revolution, a caustic feminist philosopher, and the unwed mother of Fanny Imlay (Mary’s half-sister, whose suicide coincided with the writing of Frankenstein). Relevant, too, is Mary’s own parenting tragedy, the death in less than a month of her firstborn child, an unnamed daughter (d. March 5. 1815). There are various other scandals, suicides, abandonments, and what Prof. Wolfson calls “faults of paternity” underlying Frankenstein. Victor Frankenstein, Prof. Wolfson says, “is all egotism, big on self-pity and wounded pride…. Failing to create a being whom he could bear (let alone love), Frankenstein recoils from a catastrophic wretch…. the Creature wakes into hell: reviled by his creator.”

Similar failure marks the end of Robert Louis Stevenson’s tale when Dr. Jekyll’s ambitious scientific plan derails disastrously. At the outset, however, and this is what Prof. Wolfson emphasizes, Dr. Jekyll is a ‘respectable gentleman’ who “in midlife crisis, wants to recover a youthful vitality long gone, and never fully enjoyed.” He is weary of the respectability he shares with “all of London’s drab professional men” including his friend Mr. Utterson. Prof. Wolfson takes this tale of Jekyll-Hyde doubleness to be a serious critique of 19th century culture: the code of respectability.

Respectfully submitted,

Constance W. Hassett