September 11, 2013

Advising Woodrow Wilson

J. Perry Leavell

Professor of History (retired), Drew University

Advising Woodrow Wilson

J. Perry Leavell

Professor of History (retired), Drew University

Minutes of the First Meeting of the 72nd Year

The first meeting of the 72d year of The Old Guard of Princeton was called to order by President Ruth Miller at 10:15 a.m., who called for a moment of silence in memory of those died on September 11, 2001. Don Edwards led the invocation.

The minutes of the May 15, 2013 meeting prepared by Tom Fulmer were read by Owen Leach. The President called for a moment of silence in remembrance of Bud Tibbals.

John Schmidt representing the Membership Committee reported on the members who have become emeritus, as follows:

G.P. Mellick Belshaw, Joseph L. Bolster, L. Carl Brown, John S. Chamberlin, Michael R. Curtis, Terry Grabar, John Hegedus, James M. Hester, Gene Kaplan, Warren G. Leback, Howard Mele, Charles Miller, Bradford Mills, Everard Pinneo, Harvey D. Rothberg.

Guests: Julia Coale introduced Peter Epstein, Jim Ferry introduced Charles Bowman, Claire Jacobus introducted Barbara Oberg and Bob Lowe introduced Bob Landa.

Attendance was 96.

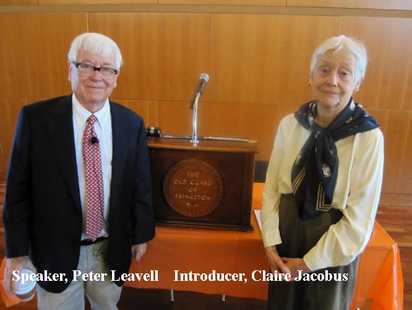

Claire Jacobus introduced Perry Leavell, professor of history emeritus at Drew University, who was historical advisor to the 2012 Princeton Celebration of The Centennial of the Election of Woodrow Wilson to the Presidency of the United States. Prof. Leavell told the story of the relationship of Edward House and Woodrow Wilson.

Briefly, House and Wilson met in November of 1911. House, a wealthy Texan whose passion was politics, was looking for a presidential candidate that he could advise. House knew William Jennings Bryant, and Wilson needed Texas to win the presidency. In his usual quick decisive mode, Wilson entered into a relationship with House. The wily politician and the intellectual seemed an unlikely pairing, but they had much in common and they were both very ambitious. They quickly became intimate friends.

When Wilson was elected in 1912, House was put in charge of managing patronage jobs and appointments for the Democrats, while House refused any appointment for himself and remained domiciled in New York City, while frequently visiting Washington. House was involved in the 1914 and 1916 elections, but his real interest was international affairs and he became Wilson’s advisor on such matters, pushing Secretary of State Bryant our of policy making.

When Wilson’s wife died in 1914, House was his companion and solace.

For three years, against the advice of House and the Secretary of State Wilson tried to remain neutral and be a mediator in World War I. House was Wilson’s personal representative who met with world leaders without any instructions from Wilson.

Meanwhile, Wilson had remarried Edith Galt and House had been displaced as the person closest to Wilson. Edith did not see the need for Wilson to have a close advisor or friend other than herself.

In 1917 Wilson suggested that House convene a group of people to consider postwar peace solutions. This group, known at The Inquiry, prepared a statement of war aims which was the basis for the Fourteen Points laid out by Wilson. Wilson and House also prepared a 1918 draft of the Covenant of the League of Nations. After the War, House was Wilson’s conduit of communications with Britain and France.

Germany accepted the Fourteen Points and House was sent to sell it to the European powers. House declared himself head of the peace process when Wilson left Paris for the US. House negotiated terms that Wilson complained of. House suggested to Wilson that he land in Boston when returning home so that Henry Cabot Lodge could witness on his home ground support for the peace plan, and that Wilson be conciliatory with the Senate. The Boston arrival did not have the desired effect, and Wilson rejected any notion of being conciliatory to the Senate. Senators were like babies with their eyes clinched shut and their mouths wide open. The two men never spoke again.

Professor Leavell’s points and observations about the relationship:

1. House thought Wilson would listen to advice, but Wilson’s prior advisors would not have agreed. Wilson had a solitary approach to decision making, had strong convictions and liked to talk about what HE wanted, but not to listen to others. Also, Wilson ignored the two year urging to go to war.

2. Was House a good advisor? He was loyal until the end, gave strong emotional support to Wilson and flattered him, but House was an amateur in foreign affairs, not well educated or well read. House and Wilson were too much alike and not complementary. Neither knew about any other country but Britain, about economics, nor was either a good assessor of men.

3. Wilson gave House no instructions; there were no written reports. In 1912 House starts a diary for future historians to know HOUSE’S contributions to affairs.

4. Not until the 1930’s did the Congress create an Executive Office of experts who were willing to remain anonymous to assist the President. In 1917 and 1919 the United States was not prepared to be a leader of the world. Its government was inadequate, weak and ineffective and some of its efforts were amateurish. This contrasted strongly with European governments.

5. House saw Wilson as a lonely man with physical weaknesses and a need for time off, emotional, passionate and given to quick decisions. Wilson was a racist Progressive, a pacifist who had several military adventures, and a Constitutional scholar who severely restricted free speech during the First World War.

6. After 1918 Wilson ran directly into James Madison’s revenge: Divided Government. On his return to the US. after the Peach Conference, Wilson also ran directly into Roosevelt and Lodge who hated Wilson. They wanted the US to have unilateral sovereignty in foreign affairs, while Wilson wanted to act in concert with other countries. TR considered such cosmopolitanism akin to being unfaithful to one’s spouse.

7. After the breakup of Wilson and House, Wilson went it alone, working 11 to 12 hour days and his health broke.

Questions:

1. On Colonel House’s background, a wealthy Southerner.

2. On Freudian analysis of Wilson. Leavell thinks that too much is made of the psychology of Wilson who was subject to many restrictions of his power and was subject to political realities.

3. House as a networker, a Southerner with all the Democrats.

4. The role of Brandeis, on whom Wilson relied for economic policy and advice but who was not nominated to be US Attorney General or for the Supreme Court because of anti-Semitic opposition.

Respectfully Submitted,

Julia Bowers Coale

The minutes of the May 15, 2013 meeting prepared by Tom Fulmer were read by Owen Leach. The President called for a moment of silence in remembrance of Bud Tibbals.

John Schmidt representing the Membership Committee reported on the members who have become emeritus, as follows:

G.P. Mellick Belshaw, Joseph L. Bolster, L. Carl Brown, John S. Chamberlin, Michael R. Curtis, Terry Grabar, John Hegedus, James M. Hester, Gene Kaplan, Warren G. Leback, Howard Mele, Charles Miller, Bradford Mills, Everard Pinneo, Harvey D. Rothberg.

Guests: Julia Coale introduced Peter Epstein, Jim Ferry introduced Charles Bowman, Claire Jacobus introducted Barbara Oberg and Bob Lowe introduced Bob Landa.

Attendance was 96.

Claire Jacobus introduced Perry Leavell, professor of history emeritus at Drew University, who was historical advisor to the 2012 Princeton Celebration of The Centennial of the Election of Woodrow Wilson to the Presidency of the United States. Prof. Leavell told the story of the relationship of Edward House and Woodrow Wilson.

Briefly, House and Wilson met in November of 1911. House, a wealthy Texan whose passion was politics, was looking for a presidential candidate that he could advise. House knew William Jennings Bryant, and Wilson needed Texas to win the presidency. In his usual quick decisive mode, Wilson entered into a relationship with House. The wily politician and the intellectual seemed an unlikely pairing, but they had much in common and they were both very ambitious. They quickly became intimate friends.

When Wilson was elected in 1912, House was put in charge of managing patronage jobs and appointments for the Democrats, while House refused any appointment for himself and remained domiciled in New York City, while frequently visiting Washington. House was involved in the 1914 and 1916 elections, but his real interest was international affairs and he became Wilson’s advisor on such matters, pushing Secretary of State Bryant our of policy making.

When Wilson’s wife died in 1914, House was his companion and solace.

For three years, against the advice of House and the Secretary of State Wilson tried to remain neutral and be a mediator in World War I. House was Wilson’s personal representative who met with world leaders without any instructions from Wilson.

Meanwhile, Wilson had remarried Edith Galt and House had been displaced as the person closest to Wilson. Edith did not see the need for Wilson to have a close advisor or friend other than herself.

In 1917 Wilson suggested that House convene a group of people to consider postwar peace solutions. This group, known at The Inquiry, prepared a statement of war aims which was the basis for the Fourteen Points laid out by Wilson. Wilson and House also prepared a 1918 draft of the Covenant of the League of Nations. After the War, House was Wilson’s conduit of communications with Britain and France.

Germany accepted the Fourteen Points and House was sent to sell it to the European powers. House declared himself head of the peace process when Wilson left Paris for the US. House negotiated terms that Wilson complained of. House suggested to Wilson that he land in Boston when returning home so that Henry Cabot Lodge could witness on his home ground support for the peace plan, and that Wilson be conciliatory with the Senate. The Boston arrival did not have the desired effect, and Wilson rejected any notion of being conciliatory to the Senate. Senators were like babies with their eyes clinched shut and their mouths wide open. The two men never spoke again.

Professor Leavell’s points and observations about the relationship:

1. House thought Wilson would listen to advice, but Wilson’s prior advisors would not have agreed. Wilson had a solitary approach to decision making, had strong convictions and liked to talk about what HE wanted, but not to listen to others. Also, Wilson ignored the two year urging to go to war.

2. Was House a good advisor? He was loyal until the end, gave strong emotional support to Wilson and flattered him, but House was an amateur in foreign affairs, not well educated or well read. House and Wilson were too much alike and not complementary. Neither knew about any other country but Britain, about economics, nor was either a good assessor of men.

3. Wilson gave House no instructions; there were no written reports. In 1912 House starts a diary for future historians to know HOUSE’S contributions to affairs.

4. Not until the 1930’s did the Congress create an Executive Office of experts who were willing to remain anonymous to assist the President. In 1917 and 1919 the United States was not prepared to be a leader of the world. Its government was inadequate, weak and ineffective and some of its efforts were amateurish. This contrasted strongly with European governments.

5. House saw Wilson as a lonely man with physical weaknesses and a need for time off, emotional, passionate and given to quick decisions. Wilson was a racist Progressive, a pacifist who had several military adventures, and a Constitutional scholar who severely restricted free speech during the First World War.

6. After 1918 Wilson ran directly into James Madison’s revenge: Divided Government. On his return to the US. after the Peach Conference, Wilson also ran directly into Roosevelt and Lodge who hated Wilson. They wanted the US to have unilateral sovereignty in foreign affairs, while Wilson wanted to act in concert with other countries. TR considered such cosmopolitanism akin to being unfaithful to one’s spouse.

7. After the breakup of Wilson and House, Wilson went it alone, working 11 to 12 hour days and his health broke.

Questions:

1. On Colonel House’s background, a wealthy Southerner.

2. On Freudian analysis of Wilson. Leavell thinks that too much is made of the psychology of Wilson who was subject to many restrictions of his power and was subject to political realities.

3. House as a networker, a Southerner with all the Democrats.

4. The role of Brandeis, on whom Wilson relied for economic policy and advice but who was not nominated to be US Attorney General or for the Supreme Court because of anti-Semitic opposition.

Respectfully Submitted,

Julia Bowers Coale